Legal language is already difficult for the public to understand and hence many professional service firms commit time and budgets to training lawyers in plain English.

Yet with native English speaking clients and prospects struggling to understand legal concepts and terms – and hearing American legal terms in TV soaps and thinking they apply in the UK, Canada or Australia – how much more difficult is it for clients and prospects for whom English is a second language?

Even if you are not targeting foreign clients, 20% of your domestic clients in the US and Australia will not speak English at home. So there’s a strong argument to say that translation should be available on every English speaking firm’s website (see methods below) even if you don’t have that many staff fluent in other languages.

Types of firms where translation is particularly important

While automated translation belongs on all professional services firms’ websites there’s certain types of firms where it is even more vital. For example:

- firms who operate in cities with large non-English speaking communities, particularly B2C / plaintiff side firms

- firms with significant immigration practices

- firms targeting international clients

Choosing appropriate languages for translation

Use population statistics to pick appropriate languages for your website

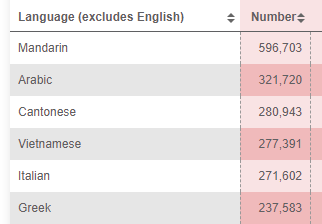

Census data is a good source of information about languages other than English that are most frequently spoken at home, although it comes out infrequently and you may therefore also want to look at trend data (for example in Australia ABS figures are compiled every 4 years and 27% of households speak additional languages at home).

US figures show 41m Americans speak Spanish at home and 3.5m speak Mandarin or Cantonese.

Australian figures show the largest non-English household numbers speak Mandarin or Cantonese followed by Arabic and Vietnamese (and for website purposes it’s worth noting that written Mandarin and Cantonese can be equally understood by each of the two communities).

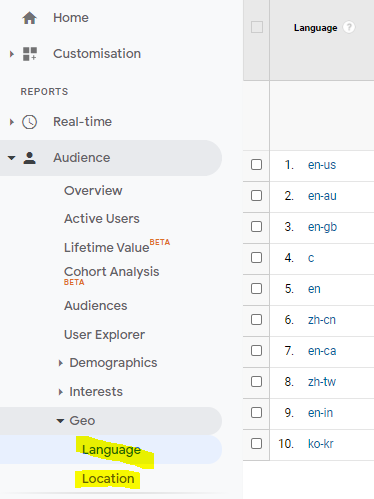

Review your language statistics in Google Analytics

Google Analytics records the language settings of browsers when people visit your website (Audience -> Geo -> Language).

However in looking at this data bear in mind that often people use English-configured browsers even if they read in different languages and therefore the ranking of languages is more useful than the absolute numbers (having reviewed this language data at Magnifirm as part of website analytics projects across multiple firms).

Types of website translation

Manual translation of website pages

Translation services normally price per word, ranging from 20c to 50c a word (figures A$). Specialised text like legal text is normally at the more expensive end of the range so translating a web page of 1000 words, like this article, would cost $500.

On average in Australia contributors to Mondaq’s syndication service write 73 articles a year or about 2.2 articles per fee earner, so manually translating all articles would be too expensive for most firms, despite the fact that analytics data shows that 74% of prospects coming to your website will visit an article first (who don’t know about your firm). That said, you could review your analytics and selectively translate say your golden articles – the handful of articles that we see driving large amounts of articles in many firms.

Generally however manual translation is best restricted to practice group pages but then bear in mind you have to deal with the further issues of

- updates to practice group pages that have already been translated

- paying multiple times for the same practice group page if you want it available in multiple languages

However with either selected articles or practice group pages the quality of the translation will be better than automated translation.

Automated translation of website pages

Whilst automated translations which use statistical or neural network techniques are not quite as good as manual translations, they are way better than no translation at all if you care about the 1 in 5 of your potential clients who aren’t native English speakers.

You don’t have to make a decision about what languages to choose and you’re betting that the trends in machine learning and processing capabilities, will see automated translations getting better and better over time (a good bet in our view).

But most importantly in looking at analytics data on legal articles we see article translations happening just as frequently as people sharing articles or going to author bios.

Free automated web page translation options

The prevailing approach for free automated translations has been the Google Translate widget. However somewhat confusingly Google phased that out in 2019 to then bring it back in mid 2020 with the proviso that it could only be used for non-commercial use.

That said we are not currently aware of any professional services firm that has had it disabled by Google. You can find the code here.

If you use WordPress as your content management system for your website there is also a free plugin called GTranslate.

Paid automated translations

GTranslate’s paid version goes further in that you can have automated translations (and even edited automated translations) which appear on separate urls – which will be more effective for SEO purposes than an embedded javascript widget. At the cheapest level this is currently about $7 a month.

Google also provides a machine translation option using volume based pricing which would be very cost effective for most professional services firms, with the first 500,000 characters a month translated free and then a charge of $20 per million characters translated. You also have much more control about how you integrate it than the free version.

Conclusion: machine translation is underutilised by professional services firms

Given the automated low cost options detailed above and the prevalence of non-English speaking households, our experience in looking at hundreds of law firm websites is that translation is underutilised in professional services firms in the UK, US, Australia and to a lesser extent in Canada.

That really should change for firms that want to attract domestic and foreign clients for whom English may not be their first language.